Page 9

A visitor from Israel who happens to visit his birthplace, the City of

Bialystok, wanders through its streets as if in a trance. Men and

women pass him by, and he does not recognize a single face. In vain do

his ears search for the sounds of Hebrew and Yiddish. And yet, behold,

these are the same houses, the same pavements where throngs of Jews

came out to watch the parade of students of the Hebrew Gymnasium and

members of the youth movements, and listen to their singing on Lag

B'Omer (New Year for Trees). Behold, these are the same streets that

became silent on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, when all the inhabitants

of the city gathered in the synagogues. It is as if it had all never

existed. The City, which was Jewish until Polish Jewry was cut down,

exists only in the memory.

Today, Bialystok is empty of Jews. Up

until the First World War, Bialystok had been predominantly Jewish (70%

in 1857), but this majority gradually shrank (51% in 1932). The

Bialystokers were mostly "Litvaks" - "Misnagdim" and intellectuals.

They consisted of industrialists and workers, merchants, doctors,

lawyers, teachers, authors, poets, community activists and party

officials, artisans, butchers, porters and carters, and also beggars.

The smoke-laden skies of Bialystok always appeared grey. The river

Biala which crosses the city, and from which its name derives, was

shallow, and polluted by industrial waste from factories. The two or

three-story houses were also grey, but the newer buildings were

finished in white plaster. The municipal park was situated in the

heart of the forest near the city, and every Sunday festivities took

place there and an orchestra played. Entry to the park was free, and

on weekdays housemaids and pauper children congregated there. It was

also loved by the youth. Bialystok was no holiday resort but a typical

industrial town. The foundations for Jewish settlement in the village

of Bialystok were laid by ten families from Grodno who answered the

invitation of the Paritz (Squire) Gottschald from Tiktin in the

Sixteenth Century. For economic reasons, Gottschald and his successors

granted benefits to the Jews who were within the boundaries of their

jurisdiction; the Jews lent them money and developed the commerce in

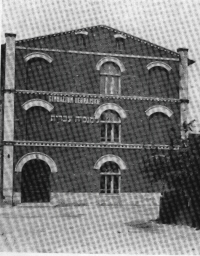

the district. (CAPTION to photo: Branitzky Palace, built in 1703, in

the style of the Palace of Versailles). For many years (till 1745),

the Bialystok community was subordinate to the Tiktin community, and

when describing its whereabouts people would say: "Bialystok near

Tiktin", and in letters: "Bialystok next to the Holy Community of

Tiktin". In the Seventeenth Century, when the District came under the

authority of the family of Paritz (Squire) Branitzky,

the community expanded greatly, and in the Eighteenth Century the Jews

of the District were granted equal rights to those of the Christians,

and the village of Bialystok became a town. The leaders of the Jewish

community participated in municipal elections, and the town's Jews

received permission to join the artists' guilds even though they paid

no taxes to the Church. In 1745 the Bialystok and Tiktin communities

separated. Jews also continued to flock to Bialystok under the

Prussian regime - from 1795 until the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 - which

abolished equal rights for the Jews, and also during the period when

Czarist Russia ruled the District (from 1809, the Peace of Vienna,

until the First World War), carrying into effect the anti-Jewish edicts

of its Prussian predecessor. Those flocking to the town were Jews who

had been expelled from their villages by edict of the Czar, and also

resourceful Jews looking for means of employment near the border. In

1842 Bialystok was declared the district capital. The Christian mayor

had two assistants, one of whom was a Jew. Two Christians and two Jews

sat on the Town Council. During the period of the Haskalah (The

Enlightenment Movement) "Reformed Heders" were established in the town,

in which the language of instruction was Russian, whilst Hebrew was

just one of the subjects being taught. (Reformed Heders - a nickname

for religious elementary schools for Jewish children in various

communities in the past, in which in addition to studying the holy

scriptures, the foundations of the Hebrew language were taught, and

elementary general subjects such as arithmetic, Jewish history, and

sometimes even reading and writing in the language of the country).

Industry came to Bialystok following the unsuccessful Polish revolt of

1830. In order to reduce imports from Poland, the Russian Government

invited German entrepreneurs to the border town, and they built its

first textile factories.

The Jews, noting their success, set up

similar factories. The number of Jewish factories grew from year to

year, and the number of Jewish textile workers increased considerably.

For most of this period the majority of Bialystok's textile factories

were under Jewish ownership. On the attachment of the Bialystockers to

the Hebrew language, Zeev Golan (Goldstein), one of the Gymnasium's

teachers, relates: "The teacher Mr. Menachem Halevi opened a Reformed

Heder in our town in which Hebrew was taught in Hebrew, and after six

months, Hebrew became for us, his pupils, virtually our mother tongue.

We asked our fathers, who were familiar with Hebrew from the Bible and

the Talmud, to speak to us in Hebrew, and thus partly Hebrew-speaking

families sprang up in the town. This was the beginning of the revival

of the language". Towards the end of the last Century, dozens of

families emigrated to Eretz Yisrael and some of these were amongst the

founders of the Moshava Petah Tikva. At the outbreak of the First

World War (1914), there were about one hundred thousand inhabitants in

Bialystok, and seventy thousand of these were Jews. A year later, in

August 1915, the German Army entered the town.

Before retreating, the

Russian soldiers burnt many of the factories, and those which were

later rebuilt and supplied their products to the German Army did not

prosper. Although money depreciated in value during the war and German

supervision was strict and efficient, Bialystok's Jews were not sorry

to part from the Czar's rule. They recalled the riots of 1906 in the

town, which were the most catastrophic of the wave of disturbances

which that year engulfed Jewish townships in Russia (seventy dead, and

ninety severely wounded). The Germans proved a disappointment in many

ways, but from several aspects the situation of the Jews improved. One

of these improvements was recognition by the authorities of the Zionist

organizations and parties which had been proscribed during the period

of Russian rule. The Zionists were provided with accommodation which

they called "The Centre".

In this building, Hebrew lessons were given,

lectures took place, and a theatrical group which called itself "The

Hebrew Stage" mounted plays in the ancient tongue. The townsfolk

exchanged books in the Centre's library, and many of them attended the

celebrations which were held there. In 1917 the authorities

requisitioned this residence, and Zionist activity then wandered from

apartment to apartment until it finally settled down (in 1919) in the

"Bet Ha'Am" ("House of the People").

1917 - the last year of the war - was a stormy one in Bialystok, as it

was throughout Russia. Young people, who were bewitched by the slogans

of the Revolution, argued with their Zionist friends in the street, in

public places, and in their homes, and on more than one occasion words

developed into fisticuffs. The "Young Zion" movement opened Hebrew

courses for adults (one of the teachers in these courses was Shimon

Ravidowitz, later professor, an historian of Hebrew literature and

Jewish philosophy, and the founder of the "World Hebrew Union"). The 2

November 1917 was a holiday in Bialystok. When news of the Balfour

Declaration became known, a large audience gathered in the courtyard of

the Crafts School and listened, with tears in their eyes, to speeches

promising that a National Home for the Jewish People would be built in

the land of their forefathers. One can assume that only a minority of

the listeners intended to be amongst the builders of the Home, but the

aspiration to emigrate to Israel certainly germinated then in the

hearts of many young people. With the signing of the Treaty of

Brest-Litovsk in 1918, Bialystok was included within the borders of a

reborn Poland. The rumours of disturbances perpetrated by the

"Hallerchiks" against the Jews of Poznan (by order of the anti-Semitic

Polish General Haller) alarmed the inhabitants of the town, and a

little while later rumours of the disturbances in the Ukraine during

the civil war reached their ears. The rioters did not reach Bialystok

that year, life in the city returned to normal, and the name of a

newspaper which was published then - "Dos Naaye Leiben" ("The New

Life") - bears witness to the hopes of its editors. The following

article was written by Yitzhak Dzivak, father of Naomi Shahar, a

graduate of the Gymnasium. It helps to explain to some degree the

phenomenon of Zionist Bialystok, and answers the question as to why the

majority of the city's Jews were Zionists, and sent their children to

Hebrew educational institutions.

|